Active Information Gathering Agent

Abstract

The ability to adapt quickly to a specific environment and the dynamics of a robot at test time is a key challenge in reinforcement learning (RL) -based locomotion. Techniques such as domain randomization, teacher-student training, and online system identification have been proposed to facilitate better adaptation. Drawing inspiration from the fact that humans actively seek out information when confronted with a new environment or given a new tool, we propose to encourage such behavior in RL agents by incorporating the expected information gain into the policy objective.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we evaluate the trained policy using MuJoCo, a platform where the environment and robot dynamics can be randomized and non-stationary. The experiments demonstrate that our method achieves a final score 2.0x higher than standard RL algorithms while utilizing less than 1/3 of the training samples.

Introduction

The ability to adapt quickly to a specific environment and the dynamics of a robot during test time presents a significant challenge in reinforcement learning (RL)-based locomotion. Humans demonstrate this adaptability by actively gathering information to connect new situations with familiar experiences, such as riding a new bike on a wild trail. Taking inspiration from this fact, we propose encouraging RL agents to actively explore unknown environments, identify key features and challenges, and adjust their policies accordingly. Agents equipped with this ability are better suited to transfer their policies from simulators to the real world, addressing the longstanding “Sim2Real” problem in robotics control caused by the reality gap in current simulators.

To achieve this, we introduce the Active Information Gathering framework, which can be applied to most RL-based agents. Rather than solely relying on actions generated from a learned RL policy, the agent autonomously decides when to explore the environment and how to adapt to it. Algorithm 1 provides an overview of this process, facilitating specialization from general knowledge to the specific problem instance the agent faces.

Naturally, we expect agents to maximize their understanding of the environment with the least interactions possible. This implies that agents should not act randomly, as certain states and actions are more informative than others in terms of gaining an understanding of the problem. Therefore, the agent has to choose actions that result in maximum information gain, defined as the prediction error of a learned world model. Intuitively, when the agent has limited knowledge about the world, its predictions will be highly erroneous. In such cases, the agent should prioritize exploring the environment, as even a single new observation can significantly enhance its understanding and improve subsequent judgments.

We have also developed two alternatives for the adaptation module, which is essentially a world model and interacts with the original RL policy. One approach involves using the information gain calculated by the adaptation module as an intrinsic reward for RL policy training. The other approach involves switching between a pre-trained exploration policy and the RL policy based on the adaptation module’s recommendations.

We evaluate the different design choices for the adaptation module and policy interaction in MuJoco. With extensive experiments, we show that our method can improve the final performance by 2.0x in MuJoCo setting with less than 1/3 of the training samples.

Literature Review

Domain Randomization

Reinforcement learning (RL) has made impressive progress in robot control with the advantage of requiring minimum knowledge of the underlying dynamics, which are usually unknown or hard to model. However, transferring policies trained in simulators to the real world has remained a central challenge due to the disparities between simulation and reality. Current simulators cannot accurately model real-world physics, making it necessary to find practical solutions. One such solution is domain randomization (DR). DR randomizes the simulation so that the reality is possibly covered by the training distribution. To be more specific, it trains policies with randomized environment and dynamics parameters and introduces noise to encompass the range of possibilities encountered in reality.

However, DR tends to produce robust but conservative policies that give the best average performance under the training distribution at the cost of optimality in specific problem instances. To address this, techniques like Environment Probing Interaction (EPI) Policy, train a separate policy that focuses on extracting environment information by selecting actions that lead to more accurate transition predictions. Another approach, Rapid Motor Adaptation (RMA), trains an adaptation module that predicts environment embeddings using information only available during training. These techniques have shown improvements in areas such as quadrupedal locomotion, in-hand manipulation, and quad-rotor control.

World Models in Reinforcement Learning

There has been a certain amount of research focusing on leveraging learned world models in reinforcement learning, particularly in the field of model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL). Early works, such as Mb-Mf, employs neural networks to directly model the one-step transition function. To account for model uncertainty resulting from under-fitted model learning, some approaches introduce Bayesian networks or utilize model ensembles to improve prediction accuracy. Recent works have tackled challenges posed by high-dimensional inputs and partially observable environments. Approaches like VPN, SOLAR, and MuZero have employed complex encoders to extract state features and represent them in a simplified latent space.

In recent years, there has been a surge of research incorporating modern architectures into the world model. For example, TAP learns low-dimensional latent action codes using a state-conditional VQ-VAE, while TWM employs the Transformer-XL architecture to capture long-term dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency.

Our method, to some extent, falls under the category of MBRL, as our Adaptation Module also models the world. It generates a compressed state representation, calculates the information gain based on prediction errors, and uses this information gain to determine which policy to apply.

Preliminaries

The goal of RL is to find a policy that maximizes the sum of future rewards. Formally, a Markovian Decision Process (MDP) is denoted as $<S, A, P, R, \gamma>$, where $S$ denotes the state, $A$ denotes the action, $P$ denotes the transition probability, $R$ denotes the reward, and $\gamma$ denotes the discount factor. At each state $s_t$, the agent takes an action $a_t$ and observes the next state $s_{t+1}=f(s_t, a_t)$ that depends on $P$ and a reward $r_t$. The goal of the agent is to maximize its final future rewards, denoted as $G_t = \sum_i \gamma^i r_{t+i}$.

Method

As outlined in Introduction, we have identified two key components in our framework that require further design. In our experiments, we aim to address the following research questions. By investigating these research questions, we aim to refine the design of our framework and prove the effectiveness of enabling active information gathering for RL agents.

- How to measure the information gain? The metric used to quantify information gain is crucial, as it determines when the agent should explore the environment and how the agent should interact with the environment to maximize its information gain.

- How to utilize the gathered information? This pertains to the interaction between the adaptation module and the RL policy. Ideally, the policy should change instantly based on the information gain, allowing the agent to gather more information, whereas the adaptation module should effectively incorporate the new information to update the information gain.

Metrics for Information Gain

In this project, we formulate the information gain from active exploration as $I = H(s)-H(s\mid o)$, where $s$ is the latent representation of state, $o$ is the current observation, and $H$ is the entropy measure. In other words, the information gain is the difference of uncertainty between the learned environment representation and the representation aided by further observation. Intuitively, when an agent has gained sufficient knowledge of the environment, its understanding of the environment will not benefit from more observations.

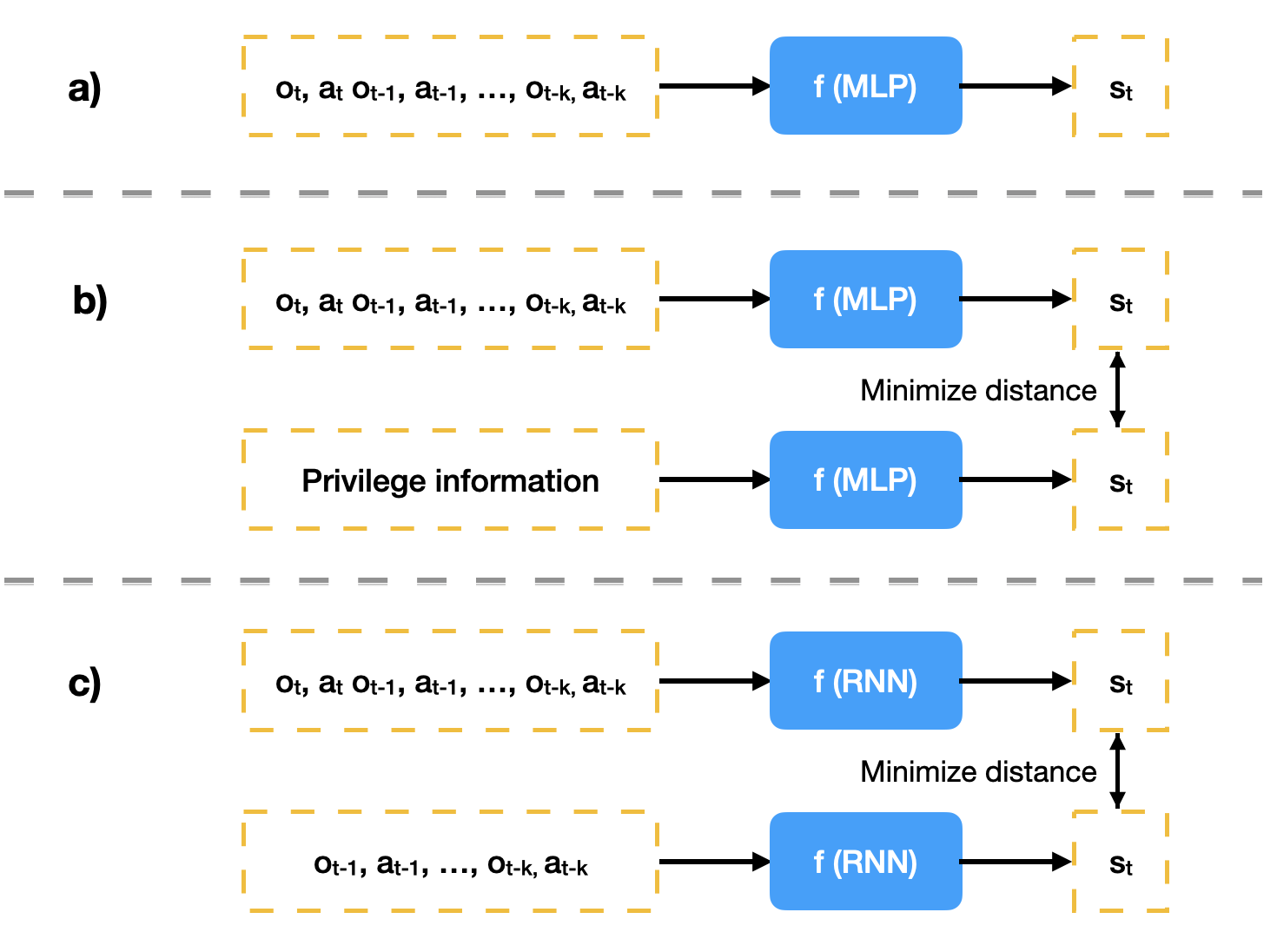

We approximate the information gain with $I = f(s_t \mid o_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, …) - f(s_t\mid o_t, a_t, o_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, …)$, where $f$, the adaptation module, can have the following three design choices.

- EPI-like approach. The latent model $f(s_t\mid o_t, a_t, o_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, …)$ builds directly on the previous trajectory and is trained together with the RL policy.

- RMA-like approach. We concurrently train a privilege information encoder $g(s_t\mid e_t)$ and a trajectory encoder $f(s_t\mid o_t, a_t, o_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, …)$. $e_t$ represents the environment information that is usually unavailable during test time. Whereas the privilege information encoder is optimized with respect to the RL policy, the trajectory encoder is optimized to minimize its prediction error with the privilege information encoder.

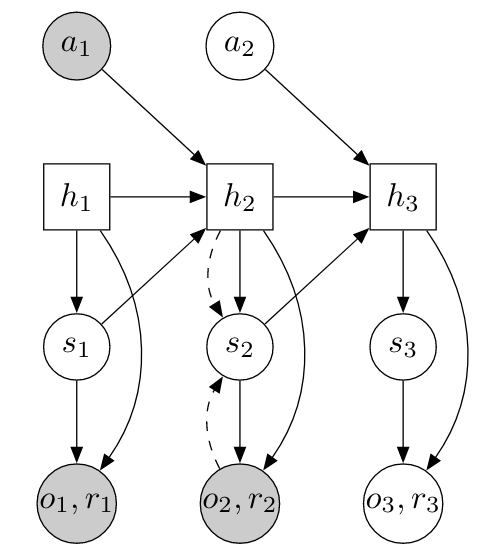

- Dreamer-like approach. We leverage the Recurrent State Space Model (RSSM) in Dreamer to encode current observation. The state in RSSM is a combination of a hidden state and a posterior state, where the former captures the time sequence with RNN, and the latter encodes the high-dimensional input into a latent representation. The RSSM thus consists of six parts:

- a recurrent model that generates the hidden states: \(h_t = f_\phi(h_{t-1}, z_{t-1}, a_{t-1})\)

- a representation model that encodes the observation and the hidden state into a posterior state: \(z_t \sim q_\phi(z_t \mid h_t, o_t)\)

- a transition model that predicts an approximate prior state based purely on hidden states: \(\hat{z}_t \sim p_\phi(\hat{z}_t \mid h_t)\)

- an image predictor that reconstructs the input observation: \(\hat{o}_t \sim p_\phi(\hat{o}_t \mid h_t, z_t)\)

- a reward predictor that predicts the reward: \(\hat{r}_t \sim p_\phi(\hat{r}_t \mid h_t, z_t)\)

- a discount predictor that predicts the discount (i.e., whether the episode ends): \(\hat{\gamma}_t \sim p_\phi(\hat{\gamma}_t \mid h_t, z_t)\)

We regard the difference between the prior state $\hat{z}_t$ and the posterior state $z_t$ as the information gain.

A sketch of the three world models and RSSM structure.

Interactions between Policy and Adaptation Module

With a well-established approximation, the information gain may aid the active exploration in three ways.

- State representation. The Adaptation Module naturally generates latent state representations, which can be utilized as observations to train the RL policy.

- Intrinsic reward. The agent uses the information gain as an intrinsic reward, so that it learns a single policy that explores the environment while simultaneously executing the task.

- Policy change. With two policies available, one focusing on identifying system features and the other performing the task, the agent determines which policy to deploy based on the information gain. The first policy can be either a random policy or a pre-trained policy specifically designed for exploration, while the latter policy represents the standard RL policy. To ensure consistency, we utilize the policy described in Point 2 as the exploration policy.

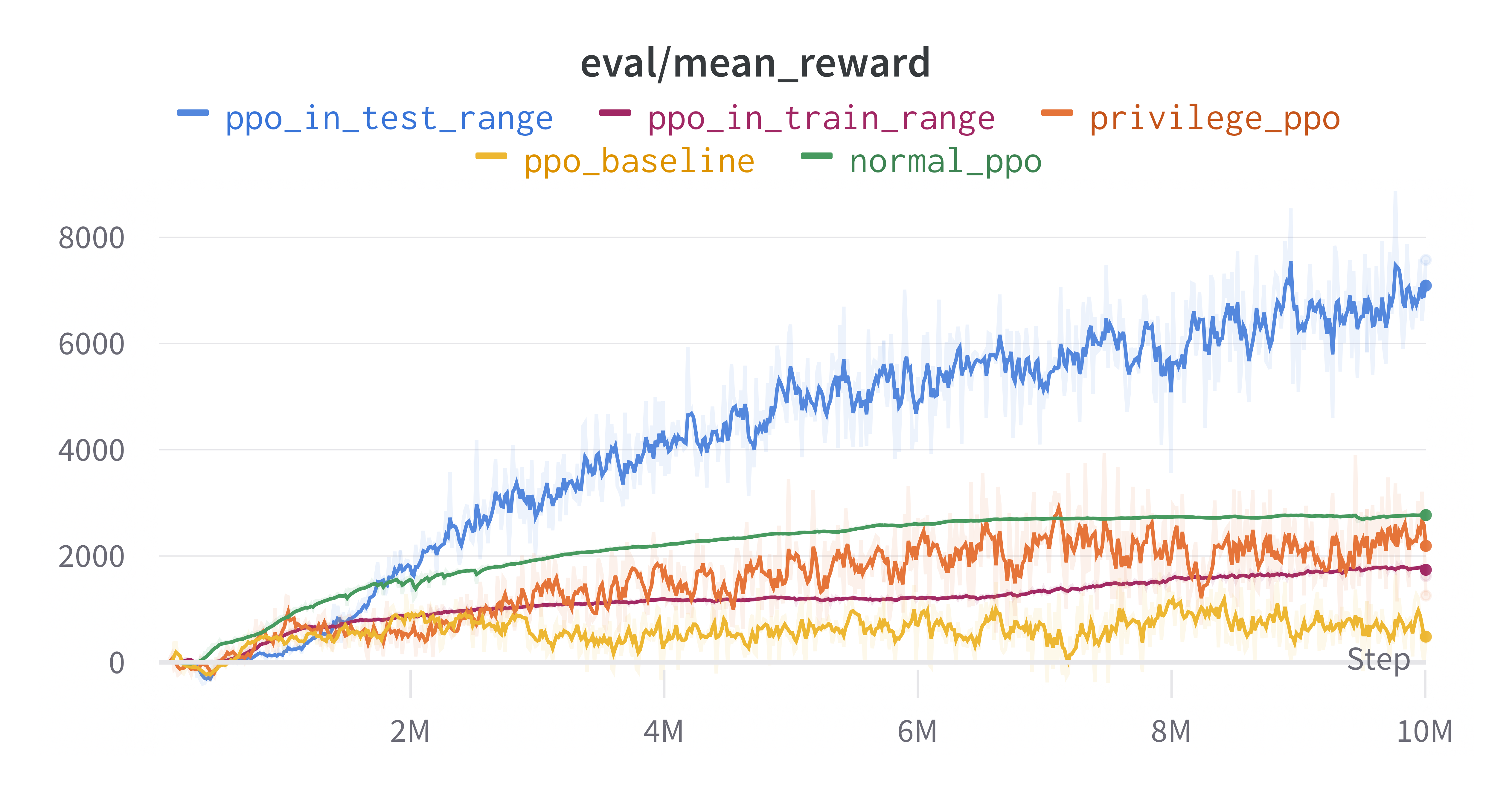

Experiments

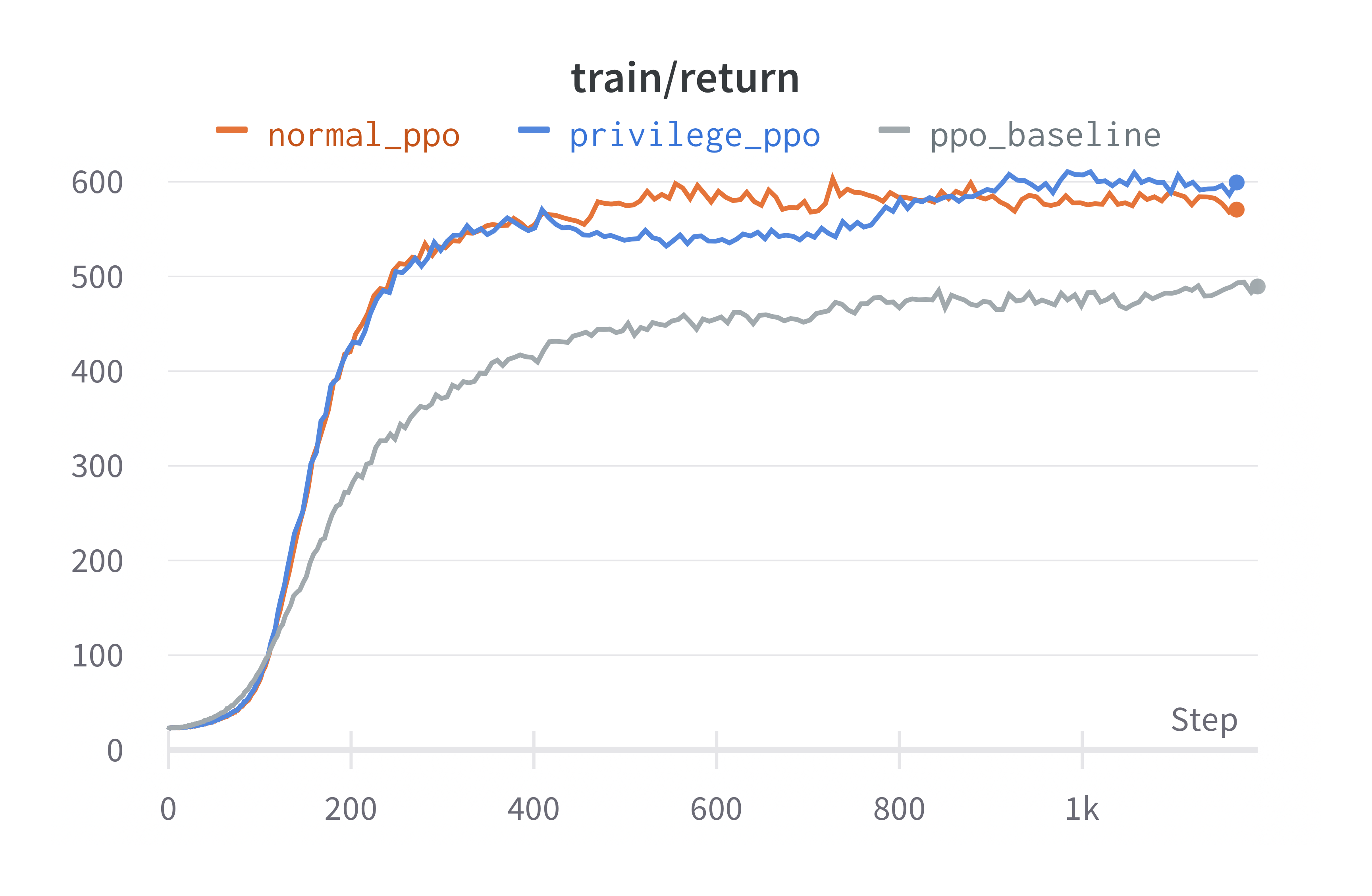

We select PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) as the standard RL algorithm for our agent and integrate different information gathering processes into the framework. We conduct experiments using the MuJoCo Half-Cheetah environment, incorporating randomized and non-stationary environment parameters. The results demonstrate that our method significantly improves the final performance by a factor of 2.0x, while reducing the required training samples by 3.2x, compared to standard RL agents.

Raw training curve.

Environmental Setup

| Parameters | Training Range | Testing Range |

|---|---|---|

| Gravity | [-30, -7] | [-7, -1] |

| Friction | [0.3, 0.9] | [0.1, 0.3] |

| Stiffness | [6, 20] | [2, 6] |

Table 1: Environmental Variations.

Table 1 presents the different environmental variations tested in our experiments. We assess the effectiveness of the environment through the following experiments:

- PPO baseline: We train the agent under 15 different environments with parameters sampled from the training distribution, and test it under 5 different testing environments.

- Privilege PPO: We train the agent under 15 different environments with parameters sampled from the training distribution, and test it under 5 different testing environments. In contrast to the PPO baseline, Privilege PPO incorporates environment parameters as privileged information and includes them in its observations.

- PPO in train range: We train the agent under 15 different training environments and test it under additional 5 training environments.

- PPO in test range: We train the agent under 15 different testing environments and test it under additional 5 testing environments.

- Normal PPO: We train and test the agent under a single training environment without any environmental variations.

As anticipated, Privilege PPO outperforms PPO baseline and PPO in train range but is beaten by Normal PPO. This observation suggests that incorporating environmental information into the agent’s observations can enhance its performance, validating our intuition. However, this environmental information is typically unavailable to the agent, necessitating its ability to explore the environment and deduce such information solely from past experiences. Additionally, PPO in test range achieves remarkably high performance, indicating that the testing domain might be comparatively easier than the training domain.

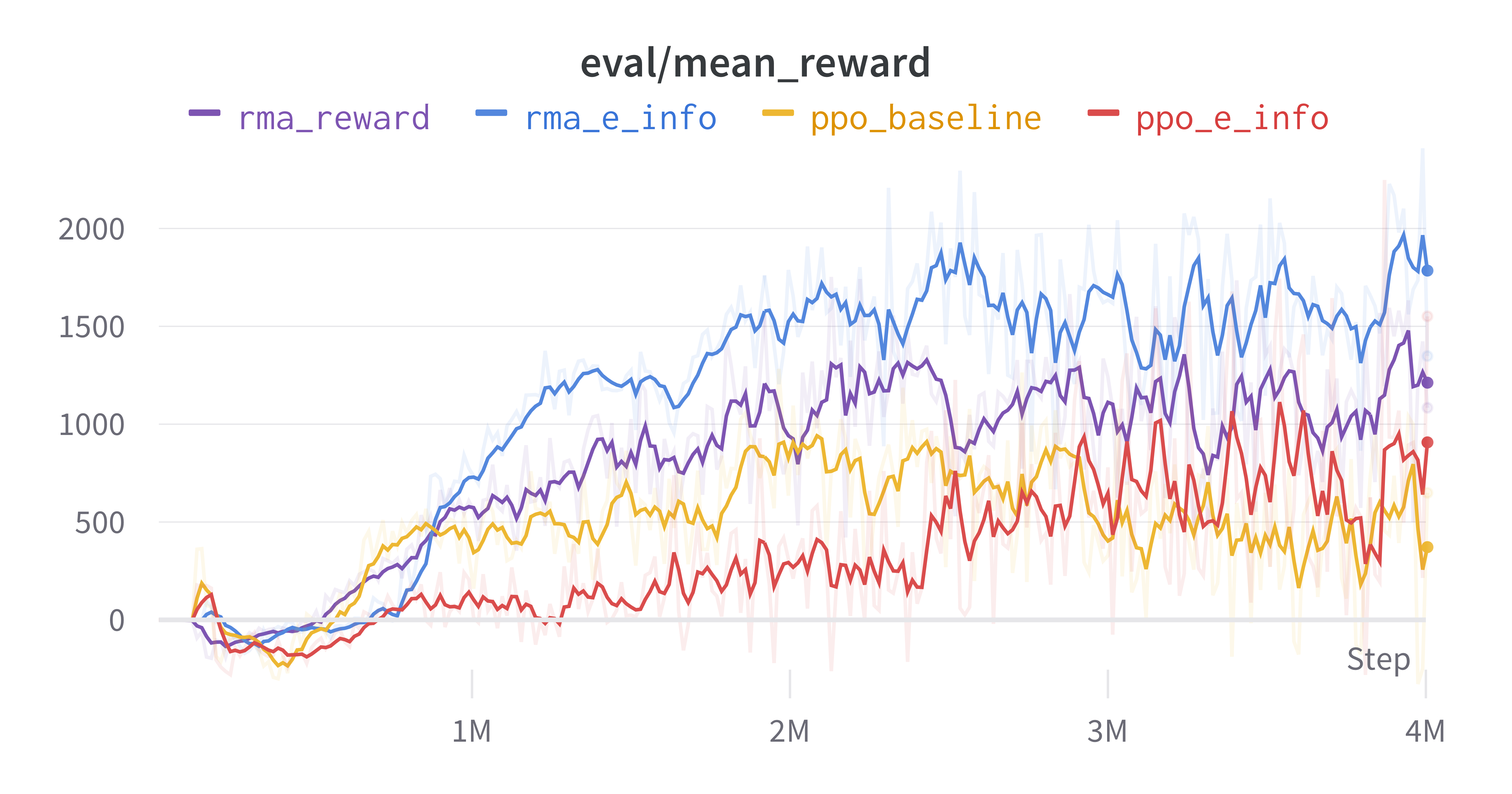

Main Results

| Metric | Interaction | Asymptotic Performance | # Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMA-like | State Representation | 2000 | 2.5M |

| RMA-like | Intrinsic Reward | 1500 | 4M |

| RMA-like | Policy Change | – | – |

| PPO baseline | – | 1000 | 8M |

Table 2: Main Results.

In Table 2, we present the main results of our study. We observe a significant 2x improvement in final performance and a notable 3.2x improvement in sample efficiency. However, we find that directly incorporating the intrinsic reward, although it smoothes the training curve, somewhat hampers the performance at convergence. One possible explanation is that the agent becomes overly focused on exploration and may neglect completing the original task. Therefore, we believe it is important to fine-tune the scale of the intrinsic reward to strike a desirable balance between active exploration and the successful fulfillment of the original task.

Possible Extensions

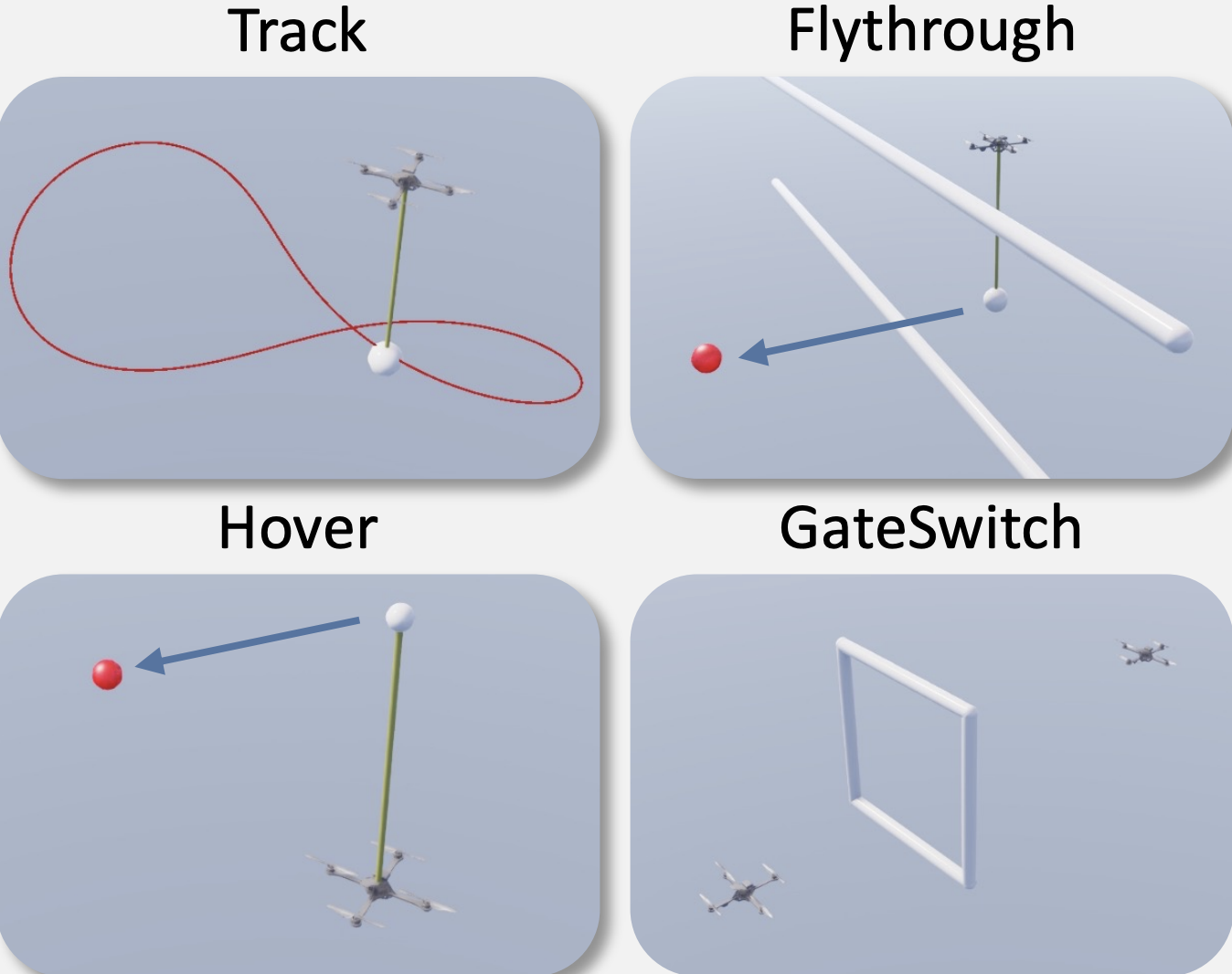

Ideally, our proposed method can tackle the Sim2Real problem and enable robot training. Therefore, we additionally evaluate a set of environments in OmniDrones, a simulator designed for unmanned UAVs.

We introduce wind disturbance into the simulator and find similar results as in Main Results. With intense wind presented, the environment becomes increasingly hard for drones to perform their desired tasks. In this case, Privilege PPO reaches a similar score as Normal PPO, and they both outperform PPO baseline.

The results suggest that the performance of real-world drones may be greatly affected by the wind, and therefore our method, which can approximate the performance of Privilege PPO, may help to bridge the gap.

Conclusion

Due to the time limit, we leave the following work for future improvements:

- Theoretical, mathematical proof of our method;

- Full experiments and complete results for all potential design points;

- Experiments in other domains, such as legged locomotion and UAV control;

- Tests in real-world scenarios.